Ambushed at the Inn: The Queensferry Incident of 1680 #History #Scotland

On 3 June, 1680, Donald Cargill was wounded in a dramatic ambush at an inn known as The Palace, or the Covenanters House, in South Queensferry. Today, the street name ‘Covenanters Lane’ records where the building stood. It only survives in photographs. Henry Hall of Haughead was mortally wounded in the same incident. How they were cornered and how they escaped from the inn, is quite a story …

The Road to the Queensferry Inn

Both Donald Cargill and Henry Hall had played leading roles in the Presbyterian Rising of June, 1679. Afterwards, both escaped into exile at Rotterdam in the United Provinces.

Cargill had returned to Scotland in early 1680 to join with Richard Cameron in raising the Covenanted standard of the Lord, almost certainly via an East Coast port like Bo’ness. In the months that followed, he appears in the context of letters to Gordon of Earlstoun’s family in Galloway. In a letter of 22 February, 1680, to Lady Earlstoun, Cargill indicates that he had not yet met or heard from Cameron. They appear to have met prior to Cameron’s letters to the Earlstouns in the latter half of March.

According to a letter from Cargill of 14 April, he was in hiding at Gilkerscleugh in Crawfordjohn parish, Lanarkshire, and had stayed at Earlstoun in the Glenkens. At around that time, Cargill and Cameron field preached together at Darmead next to Lanarkshire/Lothians boundary. From then on, Cargill seems to have been ‘lurking’ with Hall in the Fife and Linlithgowshire area. He certainly met with Cameron again on c.21 May and again at the Auchengilloch fast on 28 May.

He also appears to have met James Skene in about May, i.e., at around the time of Auchengilloch. The privy council were later convinced that Cargill had also met with John Spruell, probably at Bo’ness and at some point in 1680, after the latter’s return from Rotterdam, but Spruell refused to confess and Archibald Stewart could not confirm that they had met when he was interrogated under torture.

Henry Hall’s Road to the Inn

The evidence indicates that Hall joined Cargill a few weeks before he preached at Auchengilloch. According to Wodrow, Hall ventured home ‘this year’ and spent ‘May, and the beginning of June … in company with Mr Donald Cargil, lurking as privately as they could’ about Bo’ness and ‘other places, upon both sides of the Firth of Forth’. That places both Hall and Cargill in the context of the militant prayer societies in Linlithgowshire and Fife, that had links via the port of Bo’ness to the exiled Presbyterian leadership in Rotterdam.

From the meeting at Auchengilloch, which lies on the boundary between Lanarkshire and Ayrshire, Cameron and Cargill set off in different directions. Cameron remained in the West and soon after preached at Swine Knowe, which possibly lies by Longriggend. Cargill and Hall went east, a cross the Clyde and on to Bo’ness.

It was near there on Thursday 3 June, that they were spotted by James Hamilton, the minister of Bo’ness, and John Park, the minister of Carriden. At the time, the Scottish regime had no intelligence about what Cargill and his fellow militant presbyterians were plotting. They knew something was afoot, as had heard about their gatherings at Darmead and Auchengilloch, but they did not know what they were for. Cargill and Hall were simply high-value fugitives from the Bothwell Rising when the ministers spied them by the Forth.

Patrick Walker takes up the story:

‘when he, with Henry Hall of Haughhead, that worthy Christian Gentleman, were upon their Way from Borrowstounness to the Queensferry, these two Sons of Belial, the Curates of Borrowstounness and Carridden, walking upon the Sea-side knew Mr. Cargill, and went in haste to [Captain Robert] Middleton Governor of Blackness, and informed him.’(Walker, BP, II, 11.)

It is clear that Cargill and Hall were heading from Bo’ness for Queensferry, probably with the intention to take the ferry across to the militant societies in Fife. It is possible that Cargill intended to field preach to them, as he appears to have later altered his plans and preached in the Pentlands on 6 June.

However, while the port of Bo’ness was a relatively safe haven for them due to the presence of what were later called the Sweet Singers, the area round Queensferry was less so.

Blackness Castle lies about a mile to the east of Carriden along the Forth coast. Later, on 8 June, the privy council rewarded Carriden’s minister for his ‘good service in delating and discovering’ Cargill. (Wodrow, History, III, 206.)

The Ambush at the Inn

According to Wodrow, Middleton then sent out small search parties to locate them:

‘Upon June 3d, he ordered out a party of soldiers, to march at some distance, by twos and threes, carelessly, as if they had been upon no design; at length, by some of them, he found that Mr Cargil and Mr Hall had taken their horses, and was told the road they were riding. The governor, and a servant on horseback, presently traced them out, and kept at a little distance from them till they came to Queensferry, where the servant had noticed the house where they alighted, his master sent him off in all haste to call up his men to him, and put his horse in another house.’ (Wodrow, History, III, 206.)

The inn, also known as the Covenanters House or the Palace, lay in the heart of South Queensferry, by the harbour.

According to Wodrow, Governor Middleton bravely entered the inn on his own to delay Cargill and Hall until his men arrived:

‘Within a very little, the governor came into the house where they were, as a stranger, and pretended a great deal of respect for Mr Cargill, and begged leave to take a glass of wine with them. When they were in friendly conversation together, and the soldiers not ike to come up, the governor wearied, and threw off the mask, and told them they were his prisoners; and calling to the house to assist him, he offered to lay hands on them.’ (Wodrow, History, III, 206.)

It is clear that Walker based his account of the action at the inn on Wodrow’s account:

‘He ordered his Soldiers to come after him; he followed hard to the [Queens]Ferry, and got Notice where they lighted [at the inn], came in, and pretended great Kindness, pressing them to take a Glass of Wine, until his Men came up: Then drew his Sword, saying, They were his Prisoners, Haughhead drew Sword to defend themselves.’ (Walker, BP, II, 11-12.)

At that point, events spiralled:

‘There was none in the house would assist him, but one Thomas George, a waiter, Haugh-head was a bold brisk man, and struggled hard with the governor, until Mr Cargill got off; and then, when he was going off himself, having got clear of the governor, Thomas George struck him upon the head with a carabine, and gave him his mortal wound; however, he got out, and by this time the women of the town got together at the gate, and conveyed him out of the town. He walked a little way upon his foot, but being very sore bruised with his stroke, he soon fainted and was carried into the next country house’. (Wodrow, History, III, 206.)

Walker relays the same information, but changed the order of events in Wodrow to have Hall struck when the women rescued him. However, at this point in the story, Walker adds new information about where Hall was taken to:

‘The Women in the Town gathered; one of them gript Haughhead to save him. One Thomas George, a Waiter there [in Queensferry], behind his Back struck him upon the Head with the Doghead of his Carabin, and broke his Scull. The women carried him off, and some of them supported him to Echlen [i.e., Echline], near Half a Mile, to the House of Robert Punton my Brother-in-law, who was banished with Mr. [Alexander] Peden [in 1678, but ‘providentially’ returned]’. (Walker, BP, II, 12.)

The wounded Henry Hall was carried to Robert Punton’s farm at Echline.

Robert Punton and his family appear on the Poll Tax Roll of the 1690s: ‘Robert Punton in Aichland [i.e., in Echline] & his wife & Robert, Walter, Samuell, George Alxr, Henry, Margret & Grizzell Puntns his children.’

Henry Hall did not remain there.

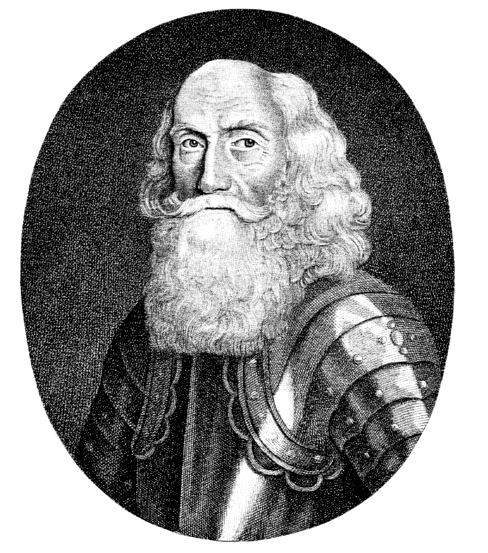

General Thomas Dalyell

The Death of Henry Hall

Wodrow takes up Hall’s story:

‘and though chirurgeons were brought [to Echline], I am told he never recovered so far as to speak to any. General Dalziel of Binns, living near by, was soon advertised, and came very quickly with a party of guards, and seized him.’ (Wodrow, History, III, 206.)

Walker adds some detail:

‘The House of Binns being near, Thomas Dalziel’s Dwelling-place (that bloody Tyrant, who was General to the Forces Twenty Years) and he having got Notice, came in great Haste and Fury, threatning great Ruin to that Family for taking in the Rebel; and carried him back to the [Queens]Ferry, and kept him all Night.’ (Walker BP, II, 12.)

When captured, Hall was near death. According to Walker, who wrote five decades after the events:

‘There is an old Christian Woman (yet alive) who waited upon him all Night, which was a weary Night, he not being able to speak to her, passing all his Brains at his Nostrils, died To-morrow [4 June] by the Way going to Edinburgh. None can give an Account how they disposed of his Corpse.’ (Walker BP, II, 12.)

Canongate Tolbooth

Curiously, Walker edited down Wodrow’s version of events, which had given more details on what happened to Hall corpse:

‘Such was his inhumanity, that though every body saw the gentlemen [Hall] just a dying, yet he would needs carry him in straight to Edinburgh, and he actually died among their hands in the way thither [via Queensferry?]. His corps were laid in the Canongate tolbooth, for three days, without burial; and though Haugh-head’s friends in and about the town, were very importunate for liberty to do their last office to him, yet that could by no means be granted. […] Some little time after, his corps were buried clandestinely in the night.’ (Wodrow, History, III, 206.)

General Dalyell found that Hall had the radical Queensferry Paper (aka. The “Fanatick’s New Covenant”) in his possession when he was captured. It was the first clear intelligence discovered that the militant presbyterians intended to overthrow the regime of Charles II in Scotland. In his History, Wodrow distanced Cargill and Presbyterians from the ‘rude and imperfect draught’ of the Queensferry Paper. However, it is clear that several of the martyrs adhered to it in their testimonies. (Wodrow, History, III, 207-212.)

Cargill’s Escape from Queensferry

Wodrow had very little to say about what happened to Cargill after he left the inn. However, Walker did have further information based on local sources. During the struggle at the Inn, Cargill escaped:

‘Mr. Cargill in that Confusion escaped sorely wounded, and crept into some secret Place in the South-side of the Town [of Queensferry]. A very ordinary Woman found him lying bleeding, took her Head-clothes and tied up the Wounds in his Head, and conducted him to James Punton’s in Carlowrie; he being a Stranger, and knew not who was Friends or Foes; for which he said he was many Times obliged to pray for that Woman. Some say, After that there was a Change upon her to the better.’ (Walker, BP, II, 12.)

Cargill probably took the most direct escape route along The Loan and hid in ‘some secret place’ on the south side of Queensferry.

One of those involved in rescuing Cargill was Margaret Wauchope. She was probably the ‘very ordinary woman’ who found him wounded in the street and brought him about two-and-a-half miles to Carlowrie, She was imprisoned on 10 June, but escaped from Edinburgh Tolbooth in October, 1680. Margaret Wauchope was clearly very resourceful, rather than ‘very ordinary’.

At Carlowrie, Cargill was placed in a barn, rather than in the house:

‘He lay in that Barn till Night, and then was conducted to some Friend’s House. Mrs. Punton gave him some warm Milk; and a Chirurgeon came providentially to the House, who drest his Wounds.’ (Walker, BP, II, 12.)

‘Niell Weddell’ a ‘chirurgeon’ (i.e., Neil Waddell, surgeon) treated the wounded Cargill on the night of 3 June. He did not hand Cargill over to the authorities, even though he was one of the most-wanted men in the Scotland.

Waddell was allegedly ‘providentially’ visiting the ‘friend’s house’ near Carlowrie when he treated Cargill. He was imprisoned in Edinburgh Tolbooth soon after Cargill’s escape and stayed there until 10 August, 1680:

‘The Lords off his majesties privie counsell having considered the petition of niell weddell chirurgeon in Queensferry prisoner upon the accompt off his pansing mr Donald Cargill doe ordaine the magistratts of Ed[inbu]r[gh] to sett him att libertie in regaird he hes found sufficient cautione to appeare befor the councell when ever he shall be called under the penaltie off ffyve hundreth merkes’. (Book of the Old Edinburgh Club, VI, 146.)

Where Was Cargill Carried?

Today, Carlowie stands on the northern edge of Edinburgh Airport. The present castle is of a later date. In 1680, the lands were held by George Drummond of Carlowrie. He was almost certainly not involved in concealing Cargill, as he was later denounced as ‘a cruel tyrant’ by the Covenanter, Alexander Reid in Uphall.

Instead, it was to the more humble house of ‘James Punton in Carlowrie’ that he was carried. Punton was later imprisoned for concealing Cargill:

‘General [Thomas] Dalziel came and called for James Punton, and took him away to Kirklistoun: When set down, the Curate there (another of the Serpent’s Brood, who inform’d him) came and accused him before the General for shewing Kindness to such a notorious Rebel, for which he was carried to Edinburgh, and cast in Prison, where he lay three Months, and paid a Thousand Merks of Fine.’ (Walker, BP, II, 12-13.)

Punton possibly lived at either Wester or Easter Carlowrie, then small farms which today lie on either side of a disused railway line. The modern Carlowrie farm lies to the east of both of them. Easter Carlowrie lies in Dalmeny parish. Wester Carlowrie lies in Kirkliston parish.

Map of Former Easter Carlowrie Farm

The Punton family may appear on the later Poll Tax Roll of 1694. It lists a ‘James Punton, Skipper, & his Wife & George Punton his son’ and ‘Janet —– his servant’ as living somewhere near Newbigging and Craigends, i.e.,to the west of Easter Carlowrie. (NA, E70/13/5/6)

It also lists a ‘James Punton, tennent, in Dalmeny & his wife, Alexr, Robert and Elspet his children.’

In 1694, the farm at Easter Carlowrie in Dalmeny parish was held by ‘James Hendersone tennent in Carlowrie’ with his wife, children and twelve servants. At nearby Craigie, one of the tenant farmers was a ‘John Punton tennant in Craigy, his wife & Gavin Punton his son’. ‘John Punton’, as the householder, also appears on the Hearth Tax Record for the parish in 1695.

Whether James Punton in Carlowrie was related to the Robert Punton in Echline who hid Henry Hall is not clear. However, it is a curious coincidence that when both Cargill and Hall were rescued, they were both initially taken to families of that surname which was not common in the parish.

It also is worth noting that the radical Cotmuir Folk had connections to both the Sweet Singers in Bo’ness, who knew Cargill in 1680, and locally to where Cargill was concealed at Carlowrie. Immediately to the north of Easter Carlowrie lies Standingstane, which appears to have been connected with the Harlaw brothers at the core of the Folk.

The “Friend’s House”

We know that Cargill stayed in a barn at ‘Carlowrie’ until after nightfall and that after that he was taken to a “friend’s house” with Mrs Punton where he was treated by the surgeon.

Some of the women who concealed him that night were also captured. The house appears to have belonged to a widow, Janet Christie, her daughter and Janet Campbell. They were set at liberty on 20 November, 1680:

‘The Lords off the Committy for publick affaires doe give warrant to the keeper off the Tolbuith to sett att liberty Jonat Crystie and hir daughter and Janat Campble who wer imprisoned upon suspicion off the resett off [Donald] Cargill in hir house she being now examined therupon’. (Book of the Old Edinburgh Club, VI, 150.)

It is not clear where “her” house lay, but presumably it was located near to Carlowrie, possibly in Kirkliston parish as James Wemyss, the episcopal minister of that parish, appears to have informed against Punton and the others involved treating Cargill. In 1688, Wemyss became Professor of Divinity at the University of Glasgow. (Fasti, I, 213.)

Three days after Cargill was at Carlowrie, he field preached in the Pentlands.

He would go on to have other very narrow escapes, at Linlithgow Bridge and especially at the Mutton Hole, before he was captured in mid 1681.

For more on Donald Cargill, see here.

Text © Copyright Dr Mark Jardine. All Rights Reserved. Please feel free to post this on Facebook or other social networks or retweet it, but do not reblog in FULL without the express permission of the author @drmarkjardine

[…] is famed for his narrow escapes from his pursuers, particularly at an inn at South Queensferry and at the Muttonhole near Edinburgh, before he was captured and executed in July, […]

The Covenanter Donald Cargill’s Narrow Escape at Watersaugh near Wishaw #History #Scotland | Jardine's Book of Martyrs said this on October 17, 2018 at 5:33 pm |

[…] Cargill’s sermon at Cairnhill/Wolf Craigs can be dated to the 6 June 1680, as Walker stated that Cargill preached there on the ‘next Sabbath’ after he was wounded and nearly captured in the dramatic Queensferry Incident on 3 June 1680. […]

Cargill’s Preaching in the Pentlands | Jardine's Book of Martyrs said this on December 14, 2018 at 2:53 pm |

[…] this while by-past, Mr Donald Cargill, since his escape at the Queensferry [3 June, 1680], is roving up and down West Lothian and farther west, and in Stirlingshire, keeping […]

Donald’s Dead Horse, the Obstinate and Cargill’s ‘Lost’ Preaching at Craigwood | Jardine's Book of Martyrs said this on December 16, 2018 at 3:56 pm |

[…] his capture must have seemed imminent – Cargill had already experienced two very close shaves at South Queensferry (June) and Linlithgow Bridge (October). However, for others, his flight was a desertion of his duty to […]

Donald Cargill, the Sweet Singers and the Darngavil Conference | Jardine's Book of Martyrs said this on December 25, 2018 at 1:11 pm |