Covenanter’s Secret Tunnel Discovered in Lanarkshire

Popular tradition is littered with stories of secret tunnels used by the Covenanters to escape capture in their houses. However, there is precious little evidence for them, except in one case, that of Major Joseph Learmont of Newholm captured in 1682…

Learmont appears to have been a veteran soldier, given the recognition of his rank of ‘Major’ by all of the sources.

He had been a tailor, who through ability, had forged a successful military career before he commanded the Covenanter’s horse on the left at the battle of Rullion Green during the Pentland Rising of 1666.

Since he was in his late seventies when he was captured in 1682, it is almost certain that he had served in the wars of the 1640s or 1650s, either in Britain, or on the Continent. However, his name does not appear either in Edward Furgol’s exhaustive list of the officers involved in the Scottish regiments during Covenanting Wars of 1639 to 1651, or in the documents relating to Scots Brigade in the United Provinces. Perhaps less surprising, is that his name also does not appear in the list of officers involved in the Scottish Army after the Restoration. The lack of evidence for Learmont’s presence in Scottish forces may indicate that he served elsewhere.

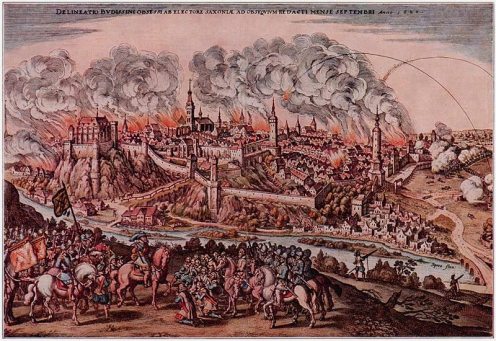

It is possible that Learmont had served in the Thirty Years’ War for a Continental power like Sweden. His apparent knowledge of tunnelling techniques may suggest that he was familiar with military mines used in siege warfare.

He purchased the compact estate of Newholm in Dolphinton parish, Lanarkshire, possibly after 1644. The estate lay by the boundary of Lanarkshire and Peeblesshire, and the sources occasionally confuse where the estate was as it lay in both jurisdictions. He was fined £1,200 under the title ‘of Newholm’ in 1662 for having complied with Cromwell’s occupation, which may indicate that he had served, like some other Scots, in the Cromwellian army in the late 1650s. (RPS, 1644/6/317.; History of Peeblesshire, 191; The Upper Ward of Lanarkshire Described and Delineated, I, 369-70.)

Map of Newholm Aerial View of Newholm

Learmont was forfeited for his part in the Presbyterian Pentland Rising in August, 1667, and his sentence confirmed by Parliament in 1669. However, thanks to the efforts of his “brother-in-law”, William Hamilton of Wishaw, his family managed to regain his former estate from 1673, even though Learmont remained forfeited. Hamilton was a key agent in a secret mission to the Covenanters at Bothwell in 1679.

‘By an attested account under his son’s hand, I find that major Joseph Learmond was under a continued tract of hardships since his forfeiture after Pentland, and was sometimes obliged to go to Ireland, and other times was under hiding at his own house, which was frequently rifled and spoiled. This year [1682] he was taken prisoner.’ (Wodrow, History, III, 410.)

In 1679, he was a senior officer in the Covenanters’ army at Bothwell Bridge and is said to have led efforts to defend the bridge. (McCrie (ed.), Memoirs of Veitch and Brysson, 480n; History of Peeblesshire, 195, 195n.)

After the battle, Learmont was identified as a ringleader of the Bothwell rebels. He appears to have returned to hiding with his family at Newholm. The surrounding area of Lanarkshire did see several field preachings in the following years, one of which, by Donald Cargill, took place very close to Newholm on 10 July, 1681. It is not known if Learmont attended Cargill’s preaching, as his later statements suggest that he may not have agreed with the Society people.

The Secret Tunnel

He was captured by Lieutenant Adam Urquhart of Meldrum of the King’s Regiment of Horse in March, 1682.

The timing of his capture is significant, as it came immediately after the killing on 3 March of a Trooper Francis Gordon, who belonged to the same troop of Horse as Lieutenant Urquhart. Gordon was shot near Mossplat in Carstairs parish. Urquhart and his troop were based at Lanark. It appears that Learmont was captured in the searches conducted as a result of the trooper’s death.

Secret passages and tunnels are a standard feature of popular culture in Scotland, although there is little or no evidence of them. Even the tunnel at Loudoun Castle, found in 1942, may well be a drain or water conduit. However, in the case of Learmont, writers of the 1680s did mention his use of a purpose-built tunnel specifically designed for his escape.

According to Lord Fountainhall:

‘On the 10 of March 1682, was Major Joseph Lermont apprehended at his oune house, neir Peibles, by [Lieutenant Adam Urquhart] the Laird of Meldrum; he had been a commander of the rebells both at Pentland Hills and Bothuel bridge. Many attempts had been made to take him formerly, but he had frustrated them all by a secret subterranean cove he had digged under his house, which, like a mine, did lead him under the ground of his yairds, and thence away to a mosse, out at which passage he formerly escaped, but was discovered this tyme.’ (Lauder, Historical Observes, 63.)

A second source, recorded the tunnel in greater detail:

‘March 1682, Major Learmont, an old soldier, and now about 77 years, and a taylor to his trade, who was at Pentland Hills in the insurrection, 1666, and at Bothwell-Bridge insurrection, 1679, was taken in his own house within three miles of Lanerk, in a vault which he diged under ground, and penned for his hiding; it had its entry in his own house, upon the syde of a wall, and closed up with a whole stone, so closs as that non would have judged it but to have been a stone of the building; it descended below the foundation of the house, and was in length about 40 yards, and in the far end, the other mouth of it, was closed with faill, having a faill dyke [i.e., a wall of turf] builded upon it, so that with ease when he went out he shutt out the faill, and closed it again. Here he sheltered for the space of 16 years, by taking himself to it at every alarum, and many times hath his house been searched for him by the soldiers; but where he sheltered non was privy to it but his own domesticks, and at length he is discovered by his own herdsman.’ (Law, Memorialls, 216-17.)

A local tradition recorded in the New Statistical Account claimed that the Learmont was betrayed by a maid servant:

‘Tradition says that the man-servant was three times led out blindfolded to be shot, because he would not betray the secret. Learmont having again taken the field at Bothwell Bridge, exposed himself anew to the fury of the persecutors. By the treachery of a maid-servant, he was at last apprehended’. (NSA, VI, 57.)

The entry on Dolphinton parish in the New Statistical Account, which was written by the local minister in 1840, described the tunnel as running to an ‘abrupt bank’ of the South Medwin:

‘For sixteen years every endeavour was made to secure the major’s person,—but he had a vault dug under ground, which long proved the means of safety to him. It entered from a small dark cellar which was used as a pantry, at the foot of the inside stair of the old mansion-house, descended below the foundation of the building, and issued at an abrupt bank of the [South] Medwin, forty yards distant from the house, where a feal dike screened it from view. When the noise of the cavalry reached the major’s attentive ear, the blade of the tongs was applied to a small aperture fitted for the purpose of raising a flat stone, which neatly covered the entrance to the vault; and before a door was opened, the Covenanter was safe.’ (NSA, VI, 57n.)

The minister’s description of the tunnel appears to be based on Law. It is clear that the minister had no physical evidence for the tunnel in 1840:

‘As these accounts, handed down for a century and a-half, had become confused, this detail was submitted to an intelligent lady, who was born at Newholm upwards of ninety years ago [i.e., in the 1740s]. She states, that the stones of the vault were, at an early period, taken to build the garden wall; therefore no trace of the retreat was found when Newholm house was last rebuilt.’ (NSA, VI, 57n.)

Is the Tunnel Still There?

Although the New Statistical Account claimed that the tunnel had been removed, it appears that some elements of the tunnel might remain in situ.

The wider landscape around the house appears to been the subject of agricultural improvements at some point in the eighteenth century, which included altering the course of the South Medwin, but it is not clear how significant the changes to its course were near the house.

Learmont’s seventeenth-century house was either incorporated into, or replaced with a new house, probably in the eighteenth century. That house was, in turn, replaced by a further house. However, it is not clear from comparing Roy’s map of the 1750s with the first OS Map a century later, if Learmont’s house and the later houses shared the same site.

There are also reports that elements of the tunnel were discovered: “In the late 1960s a secret passage or hideaway was discovered at Newholm, believed to have been used by Learmont when hiding from the dragoons.” If anyone has any information about the discovery of the tunnel in the 1960s, it would be fascinating to hear.

The Trials of Joseph Learmont

On 13 March, three days after his capture, Learmont was brought before the council:

‘The Lords of his Majesties Privy Councill, considering that Joseph Leirmont is by sentence of the Justice Court, pronounced upon the fifteen of August, 1667, found guilty of high treason for being in the rebellion in the year 1666, which sentence is ratified in Parliament upon the fifteen of December, 1669, and the said Joseph Leirmont being brought to the Councill barr did judicially confess his being in the said rebellion, as also the last rebellion at Bothwell Bridge, doe therefore give order to the Lords Commissioners of Justiciary to meet and appoint a day for execution of the said sentence’. (RPCS, VII, 361.)

On 30 March, 1682, ‘The Lords of his Majesties Privy Councill, considering that Majour Leirmont, [Robert] McClellan of Barscobe, [Robert] Fleeming of Auchinfin, ———– Haddock of Easterseat [in Carluke parish] and [Hugh] McIlwraith [in Auchenflower] are brought in prisoners as being in the rebellion, against whom there are standing sentences, doe hereby give order and warrand to the Lords Commissioners of Justiciary to call the saids persons before them and to give order for execution of the saids sentences against the forsaid persons according to law’. (RPCS, VII, 373.)

Three of the four men mentioned with him were also forfeited lairds: Robert McClellan of Barscobe in Balmaclellan parish, Kirkcudbrightshire, Robert Fleming of Auchenfin in Kilbride parish, Lanarkshire and Hugh MacIlwraith of Auchenflower in Ballantrae parish, Carrick. The fourth, Haddow of Easterseat, was almost certainly brought in by Urquhart for suspected harbouring of some of those who killed Trooper Gordon.

‘When ever any of the forfeited persons were catched in their wanderings, the old sentence in absence took effect on them, and the lords of the justiciary named a day for their execution. Thus April 7th I find four gentlemen before the justiciary, and a day named for their execution; and it seems, in these cases, a warrant was necessary from the council, who at this time assumed the powers of parliament, justiciary, and every thing which made for the carrying on of the persecution. Their sentence runs.

“By virtue of a warrant from the lords of council, the lords commissioners of justiciary, having considered the dooms of forfeiture already passed on Robert Fleming of Auchinfin, Hugh Macklewraith of Auchinfloor, major Joseph Lcarmond, and Robert M’Clellan of Barscob, for crimes of treason and rebellion; and having examined them they acknowledged they were the same persons forfeited in absence, and against whom the sentence is pronounced, by which they are ordered to be executed to death, and demeaned as traitors when apprehended: ordain Robert Fleming, and Hugh Macklewraith to be hanged at the Grass-market, Wednesday next the 12th [of April] instant, and major Learmond and Barscob to be hanged on the 28th [of April] instant, and the heads of major Learmond and Robert Fleming to be affixed upon the Nether-bow Port, and that the magistrates of Edinburgh see to the execution.”’ (Wodrow, History, III, 410.)

The sentences of execution were not carried out. Robert Gray, a fellow prisoner who was executed on 19 May, takes up the story in his letter to John Anderson, a prisoner in Dumfries:

‘P.S.—Barscob and Major Learmont got their sentence on Friday last [i.e, 7 April], to die on the 28th, and Hugh Mucklewraith and Robert Fleming had their sentence that day too, and should have died this last Wednesday [i.e., 12 April]. But they got a remission to the 28th; and it is reported that Barscob and the rest have offered to take the Test, and they have sent up to the tyrant upon that account to save their lives. As for John M’Clurg [, smith in Minnigaff,] and Robert N., there is no word yet what is to be done with them. I shall give you an account afterwards. My soul is grieved to see the treachery that is used in the matters of God among the prisoners, and their seeking sinful shifts to shun the cross of Christ. Oh! dear friend, seek to be kept steadfast in the day of trial.’ (Thomson (ed.), CW, 228-9.)

According to Lord Fountainhall, Learmont:

‘ouned before the Privy Counsell all his actings, but seimed to disclaime the wild ungoverneable Cameronian principles. A little after this, another of the ringleaders of that party, on[e] [Robert] Macclellan of Barscobe, was also seized and sent in prisoner to Edenbrugh. Being both sentenced in the criminall court to be hanged, they ware repreived; as also on [Robert] Fleeming [of Auchenfin], who was condemned for the same.’ (Lauder, Historical Observes, 63.)

Law claimed that Learmont was ‘carried before the council, and examined; confesses he was at Pentland Hills, and at Bothwell-Bridge fight, but came only there [to Bothwell] to advise the people to accept of the Duke of Monmouth’s offers he made them in the king’s name.’ (Law, Memorialls, 216-17.)

Learmont had in fact appeared among the Covenanter army with a body of Tweeddale men on 15 June, which was several days before discussions began in the council of war over whether to agree to Monmouth’s terms.

On 20 April, 1682, the council granted Learmont and the others a reprieve:

‘The Lords having considered the petitions of Robert McClellan of Barscobe, Robert Fleeming, sometime of Auchinfin, Major [Joseph] Lermonth, [Hugh] McIlvraith, sometime in Auchinflour, prisoners in the tolbooth of Edinburgh and under sentence of death for treason, they reprieve and continue in prison until 19 May next,’ (RPCS, VII, 394.)

According to Wodrow:

‘None of these four were executed, as far as I hear. Interest was made for them, and some of them got remissions, and Barscob made compliances, and was of some use to the managers afterwards. … April 20th I find a petition presented to the council, by Robert M’Clellan of Barscob, Robert Fleming some time of Auchinfin, Hugh Macklewraith sometime of Auchinfloor, and major Learmond, prisoners in the tolbootli of Edinburgh, and under sentence for treason and rebellion, for a reprieve. And the council reprieve and continue the execution of the sentence till May 19th.’ (Wodrow, History, III, 410.)

Unlike the three other prisoners before the council, Learmont failed to take the Test oath. It would also appear that the council suspected that Learmont was more deeply involved in the rebellion than he had confessed, as they did not return him to an ordinary prison.

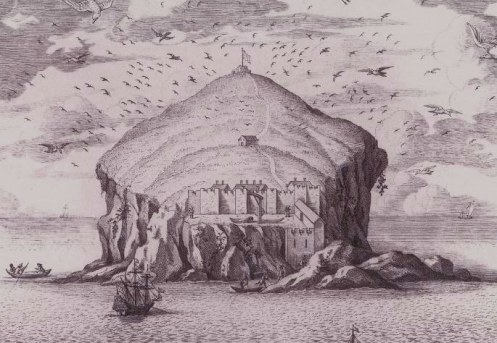

On 13 May, 1682, the council sent word to General Thomas Dalyell to transport Learmont from Edinburgh Tolbooth to the Bass Rock in the Firth of Forth ‘to keep him in sure firmance till further order’. At the same sitting, the council also read the petitions of Barscobe and Fleming of Auchenfin and granted them a remission. Learmont remained on the Bass until his release in 1687. (RPCS, VII, 427.)

According to Wodrow:

‘May 13th major Learmond is sent to the Bass, and reprieved till further orders. Barscob and Auchinfloor appear at the council-bar. The duke of York declares his majesty hath pardoned them. … By interest made for him [i.e., Learmont], at this time near eighty years of age, his sentence of death was turned to a perpetual imprisonment in the Bass, though, if he would have taken the test, he might have prevented this. There he was close prisoner five years, till falling indisposed, upon the declaration of physicians that he was in a dying condition, he was let out on bail. Next year the happy revolution came about, and he returned to his own house of Newholm, where in a little time he died in peace, in the eighty eighth year of his age.’ (Wodrow, History, III, 410.)

Learmont was ordered to be set at liberty from the Bass on 9 December, 1686, after giving bond under the penalty of 5,000 merks to re-enter prison on 9 March, 1687. The bond by John Hamilton W. S. for him was received on 18 December. Learmont was almost certainly immediately released. (RPCS, XIII, 65.)

After the Revolution, Learmont was an elder in Dolphinton parish. He died, aged eighty-eight, in 1693 and is almost certainly buried at Blacklaw Church, formerly Dolphinton parish church: According to the New Statistical Account, ‘near the door of our church, under a rustic flat stone, without even the initials of his name, the mortal remains of the pious soldier now sleep’. A modern plaque was erected at the church by the Scottish Covenanter Memorial Association in 2007.

Map of Dolphinton/Blacklaw Churchyard Street View of Dolphinton/Blacklaw Churchyard

His estate passed to his son, ‘John Learmonth of Newholm’, who was a commissioner of supply in 1704. (RPS, 1704/7/69.)

Text © Copyright Dr Mark Jardine. All Rights Reserved. Please link to this post on Facebook or retweet it, but do not reblog in FULL without the express permission of the author @drmarkjardine

Related

~ by drmarkjardine on September 11, 2014.

Posted in Bass Rock, Captain Adam Urquhart, Carluke parish, Carstairs parish, Covenanter Sites, Covenanters, Dolphinton parish, Easterseat, Edinburgh Tolbooth, Francis Gordon (d.1682), General Thomas Dalyell, Hugh MacIlwraith of Auchenflower, John McClurg, King's Regiment of Horse, Lanarkshire, Major Joseph Learmont, Newholm, Robert Fleming of Auchenfin, Robert Gray (d.1682), Robert McClelland of Barscobe, Robert N, Scotland, Scottish History, William Hamilton of Wishaw

Tags: Covenanters, Dolphinton, Early modern history, History, Lanarkshire, Scotland, Seventeenth Century, Tunnels

One Response to “Covenanter’s Secret Tunnel Discovered in Lanarkshire”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

[…] For a Covenanter’s Secret Tunnel discovered near Dolphinton, see here. […]

The “Bluidy Banner” and the Reverend John MacMillan at Haughhead in 1707 #History #Scotland | Jardine's Book of Martyrs said this on September 7, 2016 at 4:33 pm |