The Gunpowder Plot to Kill the Duke of York in 1680

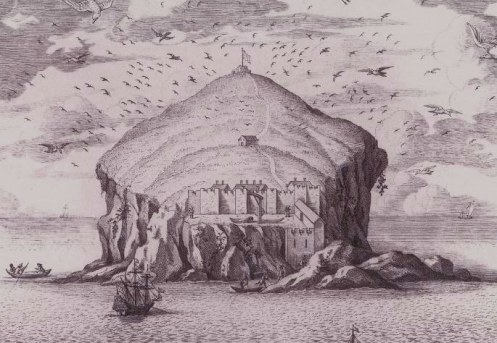

The Fortress Prison of the Bass

The Fortress Prison of the Bass

John Spreull was an ‘apothecary and druggist’ in Glasgow. He probably sold opium and other ‘cures’, which were increasing in popularity in late-seventeenth century Scotland. He was later feted as ‘Bass’ John because of his long imprisonment on the Bass Rock in the Fifth of Forth.

He was the son of a Paisley merchant, who was also called John. In 1677, he was intercommuned, after he absconded when he was called before the justiciary at Glasgow, and fled into exile. In 1680, he returned to Scotland, probably from Rotterdam, where a large Scots exile community was based.

According to Wodrow:

‘When lurking at Edinburgh, [on Friday] November 12th, [1680,] a severe search was made for Mr Donald Cargill and his followers [after the ambush at Muttonhole], and Mr Spreul was apprehended by major Johnston [of the town guard] when in his bed, and his goods he had brought from Holland seized by the party, though none of them were prohibited.

He was carried first to the general [Thomas Dalyell], and then to the guard at the [Holyrood] Abbay, where Mr [James] Skene and Archibald Stuart [of Boness, who were both captured at Muttonhole] were prisoners; with whom he was carried up to the tolbooth [of Edinburgh] next day about nine of the clock when the council was convened [on Saturday, 13 November].’ (Wodrow, History, III, 252.)

Wodrow claimed that he could not find a copy of Spreull’s interrogation, but it was reproduced in an officially-sanctioned pamphlet published in London within months:

‘In the presence of the Lords of the Privy Council the same Day [i.e., Saturday, 13 November, 1680]

John Spreull Druggist and Merchant in Glasgow, being Interrogated, Confesses that he was in the Rebellion at Bothwell Bridge [in 1679], and was in Arms.

Confesses he knows and is acquainted with Mr. Donald Cargill, but denies that he was at Torwoodhead Conventicle [in September, 1680].

Being interrogated if he owns the Excommunication of the King [at Torwood] to be just? refuses to answer.

Denies that he keeps any Correspondence with People in Holland, or brought home any Arms or Ammunition from thence.

Denies that he knows of any new Design of rising in Arms.

Being Interrogated if he owns the Declaration at Sanchar [of June, 1680], disowning the Kings Authority? denies to answer.

Being interrogated when he saw Mr. Donald Cargill? Confesses he has seen and been in company with him, but will not tell when: He says it was in Edenburgh, but will not tell where.

Being asked if he owns the Kings Authority or not? Answers he owns all lawful Authority. Being asked if the Council here sitting was a lawful Authority? Refuses to Answer.

Being asked if he thought the Killing of the Arch-Bishop of St. Andrews was a Murder? He refuses to answer thereto.

These Interrogatries and Answers being Read unto him, he refuses to Sign the same.’ (Anon., A True and Impartial Account Of the Examinations and Confessions Of several Execrable Conspirators Against the King & His Government In Scotland, 6.)

Spreull’s Version of the Interrogation

According to Wodrow, Spreull’s motive for returning from exile was ‘a design to bring his wife and family [back] to Rotterdam’ due to reports he had heard of ‘the continued persecution in Scotland, and growing divisions among the sufferers’. The latter reports refer to the divisions between the militant Society people and the moderate presbyterian ministry which had opened up in both Scotland and the United Provinces.

Wodrow knew Spreull and was sympathetic to his version of events. He reproduced ‘the substance of what passed [in that interrogation] as far as Mr Spreul could remember’ at some remove from those events. Wodrow’s version of Spreull’s interrogation contradicts that of the privy council. His presentation of the ‘substance’ of the interrogation plainly does not address the central issues of interest to the privy council in November, 1680, which appeared in the published version of his interrogation given above. What the ‘substance’ of Spreull’s version addressed was the central charge at his trial in June, 1681, which was that he had been at Bothwell.

According to Wodrow’s ‘substance’ of Spreull’s interrogation:

‘He was interrogate, were you at the killing of the archbishop [of St Andrews in May, 1679]? Ans. I was in Ireland at that time.

Quest. Was it a murder? Ans. I know not, but by hearsay, that he is dead, and cannot judge other men’s actions upon hearsay. I am no judge, but in my discretive judgment I would not have done it, and cannot approve it.

He was again urged; but do you not think it was murder? Ans. Excuse me from going any further; I scruple to condemn what I cannot approve, seeing there may be a righteous judgment of God, where there is a sinful hand of man, and I may admire and adore the one when I tremble at the other.’

According to the Privy Council, Spreull refused to answer if the killing of archbishop Sharp was murder.

Wodrow continues:

‘Ques. Were you at [the skirmish at] Drumclog [on 1 June, 1679]? Ans. I was at Dublin then.

Ques. Did you know nothing of the rebels rising in arms then in design [in 1679]? Ans. No; the first time I heard of it was in coming from Dublin to Belfast in my way home, where I heard that [John Graham of] Claverhouse was resisted by the country people at Drumclog.’

The privy council did ask Spreull if ‘any new Design of rising in Arms’ was being planned in November, 1680.

‘Ques. Was not that rebellion [in 1679]? … [Ans.] I think not; for I own the freedom of preaching the gospel, and I hear, what they did was only in selfdefence.

Ques. Were you at Bothwell with the rebels? Ans. After my return from Ireland I was at Hamilton seeking in money, and clearing counts with my customers, so I went through part of the west country army [then camped at Hamilton], aud spoke with some there, since the king’s high-way was as free to me as to other men; but I neither joined them as commander, trooper, nor soldier.’

Ques. Was that rising rebellion? Ans. I will not call it rebellion, I think it was a providential necessity put on them for their own safety, after Drumclog.’

According to the Privy Council, Spreull was in the Bothwell rebellion and was in arms.

‘This confession of his he was urged to subscribe, but absolutely refused it.’ (Wodrow, History, III, 252-3.)

Spreull’s version also completely failed to mention that the council had interrogated him over a number of issues which took place after 1679: Whether he knew Cargill and when he had last met him? Whether he was at, or owned, the Torwood Excommunication? Whether he acknowledged the King and Council’s authority and owned the Sanquhar Declaration? Whether he corresponded with exiles in Holland, had imported arms, or knew of any new rising? In short, the council were particularly interested in possible treason in 1680, rather than at Drumclog or Bothwell.

Why the council were interested in Spreull in general is obvious from the content of the official record of interrogation. However, as will become clear, it appears that they suspected him of potentially more-terrible crimes.

On the surface, the report on Spreull’s interrogation recorded in the registers of the Privy Council appears fairly unremarkable, but it begins to hint at the Council’s specific interest in his discussions with Cargill:

“Mr Spreul before the council, [Monday] November 15th, confesseth he was in company with Mr Cargill in Edinburgh [on c.Thursday 11 November], but will not discover in what house, and adds, that there was nothing betwixt them but salutations.” (Wodrow, History, III, 253.)

According to Wodrow:

‘[Spreull] being just now come from Holland, and owning he had been in company with Mr Cargill, the managers were of opinion that he could give them more information: and now being got into the inhuman way of putting people to the torture, and A[rchibald]. Stuart [of Bo’ness] being examined this way, November 15th, that same day the council pass the following act [authorising torture]’ (Wodrow, History, III, 253.)

Wodrow was slightly mistaken about the sequence of events. Stewart was tortured on Monday 15 November, but he made no mention of Spreull. However, the next day, Stewart did mention Spreull in an interrogation which was not conducted under torture. What Stewart confessed to appears to have increased the council’s interest in Spruell. Stewart had not been present when Spreull allegedly met Cargill in Edinburgh, but he did expose Spreull’s contacts with other militants in both Scotland and Holland.

On 16 November, Archibald Stewart ‘Confesses that in Winter last [i.e., of 1679 to 1680], (he remembers) he saw John Spreull in John Gib elder his House [in Bo’ness], were also present John Gib the younger, James Skene, and one Ann Stewart, but does not remember that [Donald] Cargill and [John] Spreull were together at that meeting.’

‘Being interrogated if at any time he was in the company with Mr. Donald Cargill, when John Spreull was present? He denies that he was.’

‘Being interrogated if he knows John Spreull? He declares he knows him, but doth not remember where he saw him first, having seen him so often: That about half a year since, he saw Spreull in Holland in the company of James Thomson, who lives there, and in the company of Mr [Robert] Mecquar[d], and Mr. Robert Fleeming.’

‘Confesses he saw John Balfour [of Kinloch, the assassin of archbishop Sharp,] in Holland, in company of John Spreull, where their Discourse was about Religion, and Cases of Conscience, but did not remember any particular Cases were treated of concerning their Murdering Principles.’

‘Declares that about a quarter of a year since, or thereby [i.e., c. August, 1680], he saw John Spreull in company of Mr. John Dickson (now a prisoner in the Basse) in his House in Edenburgh, where the Deponent was also present, and heard some discourse betwixt them concerning Mr Mecquar [i.e., MacWard] in Holland, and heard Spreull say, that Mr. Mecquar was sorry that some of their Party had refused to hear Mr. Robert Fleeming [at the Scots Kirk in Rotterdam].’ (Anon., A True and Impartial Account Of the Examinations and Confessions Of several Execrable Conspirators Against the King & His Government In Scotland, 9-10.)

The above passages place Spreull in the context of MacWard’s influential circle of exiles in Rotterdam and those of both Cargill’s close circle and former field preachers in Scotland. They also place him in the context of the divisive disputes within the militant presbyterian faction between those who agreed with Kinloch and those who supported MacWard. In essence, the dispute between the two wings of the militant movement was about withdrawing from the more-moderate presbyterian ministers who acknowledged royal authority. After Kinloch was excluded from communion at the Scots Kirk in Rotterdam, his supporters withdrew from other leading militant ministers, such as MacWard, who were prepared to continue to hear the ministers at the Scots Kirk. The evidence of Stewart’s confession points towards Spreull being in MacWard’s camp, i.e., on the less-militant wing of the Society people who were still in dialogue with some moderate presbyterian clergy. What is the importance of that? It is clear that Cargill had reunited the feuding wings of the militant movement after Torwood, which had made recognition of Charles II’s authority impossible for the Society people. Among Cargill’s close associates were two former exiles who been involved in the disputes at the Scots Kirk, Walter Smith, who had supported MacWard, and James Boig, who had backed Balfour of Kinloch. It is possible that the council believed that Spreull was a key go-between across the North Sea and between the circles of MacWard and Cargill, and the different wings of the militant movement.

Stewart’s interrogation on Tuesday 16 November led to a commission for Spreull and perhaps another prisoner, Robert Hamilton of Broxburn, to be tortured:

‘Edinburgh the sexteint day of November 1680. The lords of his majesties privie council having by several clear testimonies found that they have verie good reason to believe that there is a principle of muthering his majestie, and those under him for doeing his majesties service, and a design of subverting the government, both of church and state, intertained and caryed on by the Phanaticks, and particularly by Mr. Donald Cargyll, Mr. Robert Macquhair [i.e., MacWard, then in exile in Rotterdam] and others ther complices, and that John Spreull and Robert Hamilton have bein in accession thereto. They ordane the said John Spreull and Robert Hamilton, nowe prisoners, to be subjected to the torture upon such interogators as relate to these three points, to which they give much light and discovery,

first, by what reason and meanes this murthering principle is taught and caryed on, who wer accessorie to the contrivance of muthering, and who wer to be murthered, and also as to the lord St Andrews [i.e. archbishop Sharp] murther.

2do. If there was any newe rebellion intendit, by what meanes it was to be caryed on, and who was to bring home armes, or if any alreadie be bought, or to be bought, and by whom, or who wer the contrivers and promoters of the late rebellion at Bothwell bridge.

3to. Who wer ther correspondents abroad and at home, partlie at London or else wher, and what they knowe of bringing home books or pamphlets, and such particular interogators as relate to these generall:—and the saids lords doe hearby give full power and commission to the earles of Argyle, Linlithgow, Perth, and Queinsberie, the lords Rossie [i.e., George Ross, Lord] , [Lord Hatton] Thesaurer — deput, [Lord Clerk] Register, [Sir George MacKenzie of Rosehaugh, Lord] Advocat, [Richard Maitland of Over Gogar, Lord] Justice Clerk, Generall [Thomas] Dalzell, [James Foulis of] Colintoun and [George Gordon, Lord] Haddo, to call the saids John Spreull and Robert Hamilton, and to examine them in the torture upon the interogators forsaids, and such other particular particular interogators as they shall think pertinent relating to the forsaids generall heads, and to report to the council. Extract by me. Sic Subscribitur. W. Paterson.’ (CST, X, 770-1; Anon., A True and Impartial Account Of the Examinations and Confessions Of several Execrable Conspirators Against the King & His Government In Scotland, 8-9.)

The questions in the commission show that three subjects were of particular interest for the council. First, that the council suspected that assassination plots were in preparation by Cargill’s circle. Second, that they suspected that Cargill’s circle were preparing for a new insurrection. And third, that they wanted to know the scope of those suspected plots.

Wodrow found no report of Spreull’s torture in the records of the privy council ‘because nothing was expiscate by [that] torture’. An account of Spreull’s torture, unlike his earlier interrogation, was not published in the London pamphlet.

For an account of the interrogation under torture were are reliant, once again, on Spruell’s memory as recorded by Wodrow: ‘Therefore I shall, from other papers, give some account of this torture, the questions proposed, and answers given by Mr Spreul, as far as his memory could serve him afterwards to write down.’

Wodrow does not specify when Spreull was tortured, but it was presumably at the same time that the other subject of the commission, Robert Hamilton of Broxburn, was tortured, i.e., on Friday 19 November, 1680.

Tortured in the Boots.

‘[Charles Maitland] lord Haltoun was preses of this committee, and [James] the duke of York [the head of the privy council] and many others were present. The preses told Mr Spreul, that if he would not make a more ample confession than he had done, and sign it, he behoved to underly the torture.

Mr Spreul said, “He had been very ingenuous before the council, and would go no further; that they could not subject him to torture according to law; but if they would go on, he protested that his torture was without, yea, against all law; that what was extorted from him under the torture, against himself or any others, he would resile from it, and it ought not to militate against him or any others; and yet he declared his hopes, God would not leave him so far as to accuse himself or others under the extremity of pain.”

Then the hangman put his foot in the instrument called the boot, and, at every query put to him, gave five strokes or thereby upon the wedges.

The queries were, whether he knew any thing of a plot to blow up the Abbay [at Holyrood] and duke of York? who was in the plot, and where Mr Cargill was, and if he would subscribe his confession before the council?

To these he declared his absolute and utter ignorance, and adhered to his refusing to subscribe.’ (Wodrow, History, III, 253-4.)

The contents of Spreull’s interrogation under torture are clearly related to the published version his first interrogation before the council, rather than the version that Wodrow reproduced.

Wodrow’s record of the questions which were put to Spreull under torture reveals that the council suspected that he and Cargill’s circle were plotting a spectacular gunpowder plot assassinate James, duke of York.

What the privy council may have actually suspected is clarified in their proclamation against Cargill of 22 November:

‘The Truth and Reality of this Cruel, Bloody, Treasonable and Horrid Plot and Conspiracys is further evident by the Declaration and free Confession of James Skene, Brother to the late Laird of Skene, Archibald Stewart in Borrowstonnesse, and John Potter late servant to the Lord Cardrosse, who openly and in the face of Our Privy Council have avowed and declared their owning of, and adherence unto the Treasonable Covenant aforesaid found with Mr. Donald Cargill, that Execrable Declaration at Sanchar, (which Bond of Combination aforesaid, hath been owned by the said John Potter in presence of Our Privy Council, and his Subscription subjoyned to it) and that Treasonable and Impious Excommunication at Torwood; and with bare faces assert the lawfulness of Killing Us their Sovereign [Charles II], Our Dear and only Brother [James, duke of York], Our Ministers, Bishops and Judges; and that it is their Duty to Kill Us [the King] and Them, according as they shall have Power and Opportunity, and who seemed to have met together in Our City of Edenburgh on Thursday the 11th of this Instant November, to consult with Mr. Donald Cargill the best Methods for putting the said abominable and hellish Plot in Execution.’ (Anon., A True and Impartial Account Of the Examinations and Confessions Of several Execrable Conspirators Against the King & His Government In Scotland, 16-17.)

Throughout the interrogations of those taken, either at the Muttonhole, or afterwards in Edinburgh, the authorities were persistently interested in who was present with Cargill in Edinburgh and what was discussed. When Robert Hamilton of Broxburn was tortured, he, too, was ‘particularly’ asked ‘when he saw Mr. Donald Cargill, where, and what past amongst them’. (Anon., A True and Impartial Account Of the Examinations and Confessions Of several Execrable Conspirators Against the King & His Government In Scotland, 12.)

According to the authorities, Cargill’s circle had discussed the ‘best Methods’ for executing a plot at the Edinburgh meeting. It is possible that the authorities believed that the use of gunpowder to blow up York at Holyrood Abbey was one method discussed. It was, after all, only a week after bonfire night. At its best, the evidence suggests that Cargill and his associates had only discussed possible methods of assassination and possible targets. There is no evidence that Cargill’s circle were actively involved in a gunpowder plot.

On what basis the privy council believed that such discussions had taken place is not clear. Wodrow, who had an interest in vindicating the Presbyterians from involvement in such plots, asserted that ‘there was nothing in this plot and murdering design, but imaginary fears’. He may be correct.

However, it is also worth bearing in mind that Captain Robert Middleton, the governor of Blackness castle, had sent an agent, James Henderson, to meet with Cargill in Edinburgh as part of the sting operation to capture him. The authorities had mole at Cargill’s side in Edinburgh.

From Walker’s account of Middleton’s operation, it appears that Henderson spent some time in the presence of Cargill, James Skene, James Boig and others in Edinburgh. Archibald Stewart, who may not have suspected that Henderson had betrayed them, also confessed under torture that Henderson had been with Cargill and Boig in Edinburgh.

Henderson is a possible source for the alleged discussions about plots, however, there is no surviving evidence that he was the source for them. (Walker, BP, II, 13-14; Anon., A True and Impartial Account Of the Examinations and Confessions Of several Execrable Conspirators Against the King & His Government In Scotland, 7.)

Henderson’s role may also explain why John Spreull, Robert Hamilton of Broxburn and John Potter were quickly apprehended. It is hard to believe that the authorities did not exploit Henderson’s intelligence about Cargill’s contacts in Edinburgh once the trap at Muttonhole had been sprung, especially as Cargill, James Boig and possibly Mrs Moor escaped the ambush and fled back to Edinburgh.

The evidence suggests the following sequence of events. On Thursday 11 November, Cargill held meetings in Edinburgh. On Friday 12 November, the ambush at the Mutton Hole took place. Later that same day, possibly at night, John Spreull was apprehended in Edinburgh. Robert Hamilton was captured before Sunday 14 November and John Potter before 17 November. The fact that all three men that they were apprehended before they were named in any interrogation, suggests that authorities had received intelligence about them. On 19 November, Hamilton and Spreull were tortured in the boot.

According to Wodrow, the council were determined to break Spreull:

‘When nothing could be expiscate by this [torture in the boot], they ordered the old boot to be brought, alleging this new one used by the hangman was not so good as the old, and accordingly it was brought, and he underwent the torture a second time, and adhered to what he had before said. General [Thomas] Dalziel complained at the second torture, that the hangman did not strike strongly enough upon the wedges; he said he struck with all his strength, and offered the general the mall to do it himself.’ (Wodrow, History, III, 254.)

The boots did not break Spreull.

What had he confessed?

Spreull was alleged to have confessed to being at Bothwell in arms and that he knew Cargill and had met him recently in Edinburgh. Spreul had, allegedly, confessed to those points under interrogation. His torture did not, apparently, add any new information. It is important to note that Spreull refused to subscribe the records of both his interrogation and his torture. The only other evidence against Spreull was Archibald Stewart’s confession that Spreull had been at the Torwood Excommunication of the King and others. However, Stewart was executed on 1 December, 1680.

Spreull may have committed treason if he had attended the discussions about assassinations, but the case against him for that was weak and crumbling.

A Trial After Torture

‘When it was over, he [i.e., Spreul] was carried to prison on a soldier’s back, where he was refused the benefit of a surgeon; but the Lord blessed so the means he himself used, that in a little time he recovered pretty well. That same day [c.19 November] his wife came to Edinburgh, but by no means could she be allowed access to him, to help him after his torture. When he was recovered, the advocate sent him an indictment, and, in March …, he was before the justiciary;’ (Wodrow, History, III, 254.)

On 2 March, 1681, Spreull was before the court:

‘John Spreull, Appothecary, prisoner:

Indyted and accused for the crymes of treason and rebellion committed be him in the manner mentioned in his Dittay.

Persewers—Our sovereign lord’s Advocate [George MacKenzie].

Procurators in Defence—Mr. David Thoirs, Mr. James Daes.

The lords continue the dyet against the said John Spreull till the first Monday of June next, and ordaines the haill witnesses for the persewer and pannal to attend the said dyet, as also the haill assysers, ilk person under the pains of 200 merks.’ (CST, X, 725.)

According to Wodrow, the trial of Spreul was delayed because ‘the advocate’s witnesses were not ready’. (Wodrow, History, III, 254.)

Spreull Cooperates

For an alleged member of the Societies, his hearing on 2 March and his later trials are unusual in that he appointed lawyers to defend him in court. Most known cases involving Society people did not involve defence lawyers, as their use in court was tantamount to recognition of the court’s authority. It seems that Spreull, while potentially sympathetic toward the Society people, was not as dogmatic about adhering to their platform as others.

Immediately after the delay in Spreull’s trial, there are clear signs that he was prepared to assist the council’s endeavours to dissuade Society people from martyrdom. John Murray, a sailor in Bo’ness, was condemned to die on 2 March, the same day that Spreull’s trial was delayed. He had also been named by Archibald Stewart in the same interrogation in which he had named Spreull, but, unlike Spreull, Stewart had accused Murray of intending ‘to kill all that were against them who came in their way’ and of being directly inspired by Cargill’s preaching to ‘Murdering Designs’. (Anon., A True and Impartial Account Of the Examinations and Confessions Of several Execrable Conspirators Against the King & His Government In Scotland, 9.)

Within days of the trial, Spreull acted at the behest of the clerk of the privy council to persuade John Murray to petition the council for his life and wrote the petition for him. Petitioning the council ran counter to the Society peoples’ practice of not recognising the authority of the council. Although Murray’s petition also abhorred the Catholicism of the head of the council, James, duke of York, he was liberated. The blame for the offensive elements of the petition was, at least according to Wodrow, placed on its author, Spreull, rather than on John Murray.

Acknowledgment of the authority of the court and assisting the council frequently resulted in the prisoner’s life being spared. In such cases, a fine, imprisonment or liberation was often the result. In Spreull’s case, all three of those outcomes would come to pass, but not before a convoluted and contested process had taken place.

Further Trials for John Spreull

On 10 June, the diet against Spreull was deserted, but a new summons to forfeit him for the alleged treason for his being at Bothwell was immediately given to him in court. After his trial on 13 to 14 June ‘the Assyse, having considered the Depositions of thr whole witneysses, led and adduced against John Spreull, una voce finds nothing proven of the crymes contained in the Lybell, which may make him guilty.’ Spreull and his lawyers sought his liberty, but the Lord Advocate produced an act of the privy council which ordered his continued detention:

‘Edinburgh, the fourteint day of June, 1681. The lords of his majesties privie councill doe hereby give ordor and warrand to the justices, notwithstanding of any verdict or sentence returned or to be pronounced by them thereupon, upon the criminall dittay latlie persewed against John Spreull, to detaine him in prison untill he be examined upon severall other poynts, they have to lay to his charge’

The Lords Commissioners of Justiciary remitted Spreull back to prison. On 14 July, he was once again before the privy council. According to Fountainhall:

‘After all this, on the 14th July 1681, Spreul is brought before the privy council, and fined in 9,000 merks, for refusing to depone anent his presence at conventicles…; and he was ordained to be sent to the Bass till he paid it.’ (CST, X, 725-792.)

It appears that the privy council had finally got their man, but it was not for what the council had suspected him of. Initially, Spreull had been seized for plotting assassinations with Cargill. The judicial process had not secured a conviction for either his role in the alleged plots, or for being present at Bothwell. Ultimately, the council used its powers to fine conventiclers to detain Spreull. The fine was a large one, perhaps deliberately so. Spreull remained on the Bass for many years until he was liberated in mid 1687.

Why had the council aggressively pursued Spreull? Wodrow insinuates that it was because of the duke of York, the alleged target of the plot and the protest in Murray’s petition which had been drafted by Spreull. According to him, York, ‘very much pressed their going on, alleging they were at much pains about poor country people, but Mr Spreul was more dangerous than five hundred of them.’ (Wodrow, History, III, 254.)

York may, or may not, have held such an opinion. What is clear is that the authorities had publicly proclaimed the plots and published both Spreull’s interrogation and that of Archibald Stewart which incriminated Spreull. Having damned Spreull as a traitor in royalist propaganda they may have brought pressure on themselves to find some other pretext to imprison him after the treason case collapsed.

Spreull complied with the regime as far as he could, but he was a determined opponent. He resisted torture, did not depone or sign any confession. He used lawyers. And he refused to pay any fine imposed by the council for six years.

Text © Copyright Dr. Mark Jardine. All Rights Reserved.

[…] that it is their Duty to kill Us and them, according as they shall have Power and Opportunity; and who seemed to have met together, in Our City of Edinburgh, on Thursday the 11 of this instant Novemb…, to consult with Mr. Donald Cargil, the best Methods for putting the said abominable and hellish […]

Proclamation against the Fanatical and Bloody Plot of 1680 | Jardine's Book of Martyrs said this on November 23, 2013 at 7:06 pm |

[…] was also responsible for torturing prisoners suspected of treasonable plots in boots: ‘Then the hangman put his foot in the instrument called the boot, and, at every query […]

Edinburgh’s Hangman Executed, January, 1682 | Jardine's Book of Martyrs said this on September 3, 2014 at 3:51 pm |

Well written and glad I came upon this. John Spreull is my 9th Great-Grandfather. Can you recommend books for me to read to learn more about him and this time?

honoredgenerations said this on November 29, 2015 at 11:02 pm |

Hi, I would still go with an old one, James King Hewison’s The Covenanters, volume 2, as probably the most straight forward guide, but it is biased in favour of the Covenanters. For from modern works, Tim Harris does a good two volume history, Restoration and the other one, Revolution. For plots, Richard L Greaves, Secrets of the Kingdoms, is good but very expensive. Mark

drmarkjardine said this on November 29, 2015 at 11:13 pm |

Here are all the posts that mention him https://drmarkjardine.wordpress.com/category/by-name/john-spreul/

drmarkjardine said this on November 29, 2015 at 11:44 pm |

[…] drmarkjardine.wordpress.com […]

11 Surprising Facts You Never Knew About the World - Deepest said this on December 16, 2015 at 10:38 pm |

[…] captured in November, 1680, soon after Cargill was ambushed at the Mutton Hole and the supposed gunpowder plot against the Duke of York, when Cargill’s network was […]

Isobel Alison Transported to Edinburgh in 1680 #History #Scotland | Jardine's Book of Martyrs said this on November 21, 2016 at 8:16 pm |

[…] The following letter was sent, probably by Donald Cargill, to Archibald Stewart, from Bo’ness, and John Potter, from Uphall, prior to their execution in Edinburgh on 1 December. 1680. Both men had been captured after the Mutton Hole incident and were suspected on the basis of dubious evidence of being part of a gunpowder plot to kill James, Duke of York. […]

Letter to the Martyrs, Archibald Stewart and John Potter, November, 1680 #History #Scotland | Jardine's Book of Martyrs said this on June 8, 2017 at 11:06 am |

[…] Cargill in a house in the Westbow of Edinburgh when, allegedly, treasonable discussions to conduct a gunpowder plot against James, Duke of York, took place. On Friday, 12 November, he was captured at the Mutton Hole with Archibald Stewart, […]

The Covenanter’s Poisoned Musket Ball #History #Scotland | Jardine's Book of Martyrs said this on July 24, 2017 at 6:15 pm |

[…] to take away that vile and malicious aspersion, which they cast upon us; charging us with an intention to have murdered the Duke of York and others with him; I declare I had never such a principle as to murder any man, neither did I ever hear of it till […]

Testimony of John Potter Executed at Edinburgh’s Mercat Cross 1 December, 1680 #History #Scotland | Jardine's Book of Martyrs said this on December 1, 2017 at 9:47 am |

[…] (24 October) and near Fauldhouse (31 October). They were his last two preachings in 1680, as after an alleged Gunpowder Plot to kill the Duke of York and his near capture at the Mutton Hole on 12 November he fled into exile in England and did not […]

Donald’s Dead Horse, the Obstinate and Cargill’s ‘Lost’ Preaching at Craigwood | Jardine's Book of Martyrs said this on December 16, 2018 at 6:57 pm |

[…] The Privy Council suspected that Hamilton of Broxburn had knowledge about the ‘Phanaticks’ intentions to murder Charles II, or his brother the Duke of York, who had recently arrived in Scotland, and those ‘doeing his majesties service’, such as the privy councillors which Cargill had excommunicated at Torwood. Two days later, on 16 November, a commission was granted by the Privy Council for Hamilton of Broxburn and his fellow prisoner John Spreull to be tortured as part of their investigation into an alleged Gunpowder plot: […]

Cargill’s Preaching at Largo Law and the Assassins’ Cave | Jardine's Book of Martyrs said this on December 22, 2018 at 8:01 pm |

[…] Hamilton in Broxburn was tortured in the boots as one of those suspected of involvement in a gunpowder plot in late […]

Suspected Traitor Robert Hamilton in Broxburn is Liberated in 1681 #History #Scotland | Jardine's Book of Martyrs said this on June 22, 2019 at 2:49 pm |