The Wigtown Martyrs: Provost Cultran’s 73-Day Absence After the Trial #History #Scotland

In the Nineteenth Century, one prominent historian claimed that Provost William Cultran was ‘in all probability’ absent from Wigtown when the two female martyrs were condemned to be drowned at a trial in the burgh in 1685. In other words, he claimed that the documents ‘in all probability’ proved that Cultran was not present at the trial of the two women, when at least one Presbyterian source definitely said that he took part in the trial.

However, here we are dealing with the historian and neo-Jacobite, Sheriff Mark Napier, who was a denier of the historical evidence for the Killing Times at every turn.

It is worth saying that again, as I believe this to be true. Napier was a Killing-Times denier.

One has to ask what evidence would Napier have accepted for the historicity of the Killing Times? As far as I can tell, the only field death of the Killing Times that he accepted was when his beloved John Graham of Claverhouse wrote in a letter that he actually had John Brown in Priesthill shot by a firing squad. Any other summary execution in the field that crossed his path, he dismissed. There are 92 or 93 summary executions mentioned in the historical sources.

What Napier picked up on in terms of Cultran’s absence seems to be a minor point in case of the Wigtown Martyrs, but that was his strategy. As a good lawyer, he chipped away at every detail in order to cast doubt on the broad evidence and accepted fact that the women were drowned.

Was he right about the fact that Cultran was “in all probability” not at the trial? Let us look back through the evidence …

The Trial

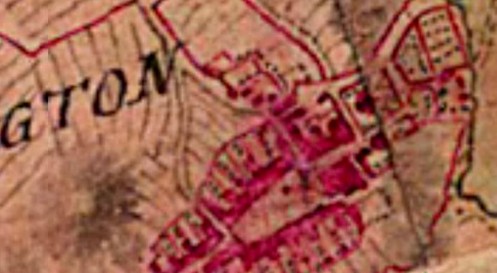

On 13 April, 1685, a prestige event took place in Wigtown, a justiciary court was held in the burgh. It condemned two women to death by drowning, Margaret McLachlan and Margaret Wilson. The trial was organised under a judicial commission granted to Colonel James Douglas, a senior military officer who had proven highly effective in the field. Those facts are beyond dispute.

The court was presided over by three judges, the number that was legally required in the absence of Colonel James Douglas. They were Sir Robert Grierson of Lag (sheriff), David Graham (sheriff-depute of Galloway and the brother of John Graham of Claverhouse) and Captain John Strachan. All three had been commissioned to hold a court in Galloway if one was called under the wide-ranging powers granted to Colonel Douglas, the brother of one of the most powerful men in the land, Queensberry.

Doubtless having been forewarned by Colonel Douglas in writing that such important figures were coming to Wigtown to dispense justice, it was almost certainly incumbent on the burgh elite, including Provost William Cultran, to be present and put on a “good show”. That was their job. This was the power of the Crown being displayed in Wigtown. It was not just a judicial event, an expression of royal power, it was a social-power event where the rituals of burgh and regional hierarchies were on public display.

As the commission to Colonel Douglas ran from 27 March to 20 April, he could have written to Wigtown at any point after his commission began and a few days before the date for the judges were to sit on 13 April. Given the logistics of organising a justiciary court – witnesses had to be called, the event organised, indictments drafted, etc.– he probably wrote to Wigtown and those concerned in the court earlier in that window to give the Provost, the burgh and judges etc., time to prepare and travel for the trials.

The Actions of Douglas

We know that the primary motive for Douglas’s commission of 27 March was to respond to rebels openly moving in force through Ayrshire. On 22 March, an illicit muster of 260 armed Society people had been held at Cairn Table and just beforehand the seat of the Earl of Dumfries at Lochnorris was raided by rebels for arms. Both of those sites lay near Cumnock, the latter very close to it. The rebels evaded capture.

Douglas and garrison commanders were sent into the field on 24 March with orders ‘immediately to punish the commons who did not inform against them’. The judicial commission to Douglas followed three days later. His first duty was to deal with those who were suspected of either assisting the rebels, or not reporting their presence. To that end, he held a court that tried and condemned four men at Cumnock on 3 April. They were sentenced to be hanged, but as they were prepared to take oaths (recognising royal authority) their sentences were not carried out and they were ultimately pardoned on 25 June after they had taken oaths.

On the following day, 4 April, a prisoner, Thomas Richard, was brought in from the field to Cumnock. Richard had hidden fugitives and refused to take oaths, such as the Abjuration oath that renounced the militant Society people’s ‘war’ of assassinations against crown officials. Douglas appears to have exercised his powers as a commanding officer to press the abjuration in the field. He had Richard summarily executed by firing squad on the following day. Firing squad was a summary military-judicial, rather than a post-trial judicial, form of execution. That tells us which legal jurisdiction Richard was executed under.

Where Douglas went before he attended the Privy Council in Edinburgh on 21 April, the day after his judicial commission expired, is not clear. It is possible that he went to Dumfries, as he put an oath to Euphraim Threpland, who was imprisoned there, and she appeared before him at a court held in the burgh at some point prior to 5 May. (Wodrow, History, IV, 327.)

Douglas’s judicial commission granted him:

‘full Power to him to call Courts at such Times and Places as he shall find expedient and then and there to create Clerk, Sergeants, Dempsters, and other Members of Court needful, [etc.]’.

We do not know how many courts Douglas ordered, beyond those in Cumnock, Wigtown and probably Dumfries. Whether Douglas ordered a court depended on the local need for one, which in practice relied on the head burghs of each locality having Presbyterian prisoners in their tolbooths.

Cumnock, which was not a head burgh of a shire, was chosen as the location for a court to make a statement in the locality where the armed rebels had acted.

His commission listed ten shires (and judges in each) where he could potentially have called a court. Among those areas was Galloway that included both Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire, which had separate head burghs. It would have been impossible for him to attend courts in all eleven shires during his twenty-four day commission. Douglas certainly ordered a court to be held in Wigtown under his commission, but none of the Presbyterian sources which specifically refer to that court mention him as being present.

Douglas also held the power to appoint court officers as required. We know from later sources the names of at least two members of the burgh elite who were involved in the Wigtown trial of the women. They were Provost Cultran, probably as the dempster (i.e., doomster) as he ordered the women to receive their sentence on their knees, and Baillie John McKeand, who possibly served on the jury.

The Provost must have been appointed by Douglas as a court officer in advance of the trial, i.e., prior to Monday, 13 April.

The Next Day in Wigtown

On the following day, Tuesday 14 April, the judicial show was over in Wigtown, but a further public event followed when a proclamation announced that the recently elected members of Parliament were to attend Queensberry, the chosen representative of the King, at the riding of Parliament in Edinburgh. Parliament would begin in nine days time on Thursday 23 April. Did the newly elected member of Parliament for the burgh of Wigtown, Provost Cultran, attend that proclamation? What do you think? This was his civic moment. It was his public send off. What we do know is that the Provost no longer attended the burgh council from that exact date.

On the following day, Wednesday 15 April, the burgh’s hangman launched a pay dispute over his having to remain in the tolbooth with the prisoners (including the two women), at an extraordinary meeting of the burgh council at which Cultran was not present. It is clear that he had work with the prisoners in the tolbooth following the trial. The council agreed to pay him, presumably as they expected him to remain with the prisoners who were then still in the tolbooth. We know that he was owed wages, as the hangman refered to that matter ‘at ane frequent [rather than extraordinary council] meiting efter the provest’s retourne’ from Edinburgh in late June.

The Logistics of Parliament

Attending Parliament in Edinburgh required organisation. Cultran had to pack a lot. His servants had to get everything he needed onto at least one cart and horses. Who knew how long this parliament would last? As it turned out, he was out of town for 73 days. He had to have his finest clothes and more for every session, daily clothes, the burgh insignia, all the papers required, food for the journey, lodgings in Edinburgh established, everything he needed to politick there. Who knows how long his packing list was, but we can be certain it did not fit in a several saddle bags.

Everything that he needed had to be transported to Edinburgh. He did not simply get on horseback and go. He also had to make it there, unpack, establish himself in his lodgings and be ready for the riding of Parliament when it opened on 23 April. There the pecking order and display of the procession for the rising of Parliament mattered and was the subject of intense disputes.

Cultran had nine days to make it to Edinburgh for the riding of Parliament. We know from the prisoner transportation of Gilbert McIlroy a couple of months later, that it took at about six days (excluding three extra days he spent at Barr Kirk) for a mixed convoy of horse, foot and cart to make it to Edinburgh. If the Provost left on 14 April, as a later burgh document indicates, he may have made it with a couple of days to spare before the riding of Parliament. That makes sense. It was not an event he could miss, as he publicly represented Wigtown and its ancient burgh status at it. We know that he made it there as he was present at the opening of Parliament on 23 April.

That means that Provost Cultran was not present in Wigtown when the execution of the two women took place. He had no role in the actual execution of the two women.

Cultran’s Return

After Parliament ended on 16 June, Provost Cultran returned to Wigtown. That entailed the same logistical tasks in reverse order as the journey to Edinburgh. He officially reappeared in Wigtown on Thursday 25 June, which is, coincidently, the same time frame of nine days that that he had allowed for his journey to Edinburgh. We know that Cultran returned then, as he immediately claimed his expenses:

‘Wigton, June 26. 1685: Convened, the Provost [Cultran], the two Bailies, and of the [burgh] Council, William Clougstoune, Adam Kyneir, Michel Shank, John Dunbar, John M’Keackan, George Kincaid, Antony M’Clure, Antony Dalyell, Adam M’Kie, Alexander Gordon, Mr James Broune, John M’Keand:

The which day, William Coltrane, Provost, who was elected Commissioner to the Parliament, having returned, has made his report as follows: viz. That he was seventy-three days absent, and that he gave in three rex-dollars and ane half dollar with his commission; and that he gave ane dollar to Bartholomew M’Kean for his adverting to the town’s papers; which in haill extends to the sum of two hundred twenty and four pounds and fifteen shillings Scots money, at ane rex dollar ilk day, conform to the former act; which sum of two hundred twenty and four pounds and fifteen shillings Scots money, the Magistrates and Council oblige them and their successors in office to content and pay to the said William Coltrane, Provost, his heirs, executors or assignees, betwixt this date and the term of Lambas next to come, so far as the treasurer shall not produce receipt thereof.’ (Napier, Memorials and Letters, II, 97-8.)

The evidence is precise in placing Provost Cultran in Wigtown on the day of the trial of the two Wigtown martyrs on 13 April, as he left the next day. It is clear that he was not present when they were drowned, as he did not return until 26 June. After his initial role as a court officer, Cultran probably played no further part in their case or their execution.

Contra Sheriff Napier

When Napier examined some, and only some, of the same evidence in the Nineteenth Century, He reached a different conclusion about Cultran’s 73-day absence to that outlined above.

He described the evidence for Cultran’s absence as ‘very handsomely [getting him] out of the scrape’, as he was absent at Parliament when the women were executed.

That is true and is not disputed. Not one of the Presbyterian sources places Cultran at their execution.

However, it does not get Cultran out of his role at the trial, which the Presbyterian sources say he was present at on 13 April.

Napier decided that when Cultran returned did not necessarily imply that he returned on 26 June, when he claimed his expenses, and that he had probably returned ‘a day or two’ earlier.

He may have. He may not have, but we know that it took around six of the nine days before he appeared at the burgh council for his party to return to Wigtown after Parliament. Cultran probably already had a couple of days in hand before he attended the burgh council.

Napier also claims that Wigtown’s burgh council received Cultran’s report ‘the very day after his return’. However, Napier’s shifting of Cultran’s return by a single day is not based on any historical evidence.

Napier knew that the evidence directly stated that Cultran returned after 73 days on 26 June, i.e., since departing on 14 April. He slyly added an extra day, perhaps hoping that his readers missed that.

Napier did that in order to push back the date of Cultran’s departure to the day of the trial.

Thus he falsely concluded that ‘in all probability’ that the Provost was ‘absent from Wigton when the women were condemned’ on 13 April.

The historical evidence says that Cultran was present in Wigtown on the day of the trial that condemned the women, as he left on 14 April, the day after it finished.

The more you examine Napier’s arguments, the more his case against the drownings happening falls apart.

It is worth remembering that almost nobody disputed the evidence for the reality of the Killing Times until Napier did well over a century-and-a-half later.

Text © Copyright Dr Mark Jardine. All Rights Reserved. Please link to this post on Facebook, Twitter or other social networks, but do not reblog in FULL without the express permission of the author @drmarkjardine